- Home

- Susan Coll

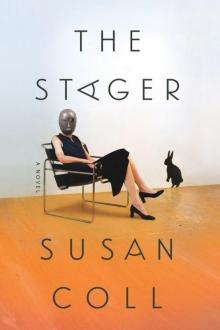

The Stager: A Novel Page 2

The Stager: A Novel Read online

Page 2

“Oh, nothing too radical, just a bunch of little stager tricks. Mostly just depersonalizing. People want to imagine their own families living here, and it’s hard when they see all of your things, like your toys or your pictures.”

“What are some of the ‘tricks’?”

Before the Stager can answer, we hear voices moving up the staircase, and then, all of a sudden, there are three people standing at my door. One of them is Amanda, the Realtor. She is in the middle of a sentence about the square footage of my bedroom, but then she sees me and the Stager sitting on the floor and she stops talking and says, “What are you doing, Eve?”

The Stager puts the little spoon down and says, “I’m helping the child clean up her room.”

Amanda says “Oh,” and then turns back to the people she is with, who are both very large. The man is wearing a blue suit but no tie, and the lady has on a dress with orange flowers. I can’t tell if the flowers are enormous or if they just look enormous because of the size of the lady. I also can’t tell if the man she is with is her husband or her father.

“We could paint, maybe knock out those bookshelves, change the carpet, and turn this into Toby’s room,” the man says.

“Or we could put Briana in here and keep the décor,” the lady replies.

“No, I think we’d need to paint, no matter who goes in here. These colors are pretty hideous.”

It’s true; we decorated my room three years ago, back when I was in second grade and was really into pink and purple. But I would like these people to get out of my house. The idea of Toby or Briana living in my room, whoever they are, makes me want to scream.

“By the time you come back on Sunday, these colors will be gone. You’re getting a sneak peak,” says Amanda. “This is the first showing. It’s not technically listed yet. We’re cleaning and painting, so it will be spick-and-span by Sunday.”

No one has said anything to me about painting my room.

“Wasn’t this already on the market?” the lady asks. “I looked at a couple of other places in The Flanders and I’m pretty sure I noticed a sign out front, but, if my memory is correct, it was out of our range, so I hadn’t bothered to look.”

“Do you smell something funny?” the man asks, making a sniffing noise. He looks at the lady, who is his daughter or wife, but she doesn’t say anything. Then he sniffs again, twice in a row, more conspicuously. Amanda walks over to my window and pulls it open. A gust of wind makes the lace curtains puff out, and we watch as they slowly settle back against the wall. Then the people come into my room and walk around, inspecting things, like we aren’t even there. The lady opens the closet and looks inside and pushes my clothes to the back of the rack. The man walks over to the window and stares out at the pool. Then he taps on the wall behind my bed and says something about its being “load-bearing.” They all go into the bathroom at the same time, and I hear the cabinets being opened and closed and the sound of the water running. Then they come back out and stand in my room again.

“We’re giving this a little TLC and a fresh start,” Amanda says. “The market has been pretty volatile, and the last Realtor priced it wrong, plus it needed a bit of sprucing up. But this neighborhood is dynamite, and things are getting better every day—as I’m sure you know, since you’re shopping. Home prices in this area rose by seven percent last year.”

“Really?” says the man, surprised. “What about that new development right behind here—that Unravelings place I keep hearing about? I thought it was in foreclosure, and bringing the whole neighborhood right down with it.”

“Unfurlings,” says the lady, who is maybe his wife.

“That’s an unfortunate situation, but it’s had no impact on values in this area, generally,” says Amanda. “It was a poorly conceived idea for some New Age baby-boomer living concept. Unwind, unfurl! Live like hippies, raise llamas, grow your own vegetables, listen to NPR, and live in three-million-dollar dream houses.”

Amanda laughs, but everyone else is silent, like maybe they don’t get why that’s funny. “They’ve organized the place like it’s a college campus, or a library, or some Marxist commune,” she continues. “Each according to his interests! They have fiction and nonfiction enclaves, a history enclave, music, visual arts, etc. Great idea, apart from the fact that no one can afford to live there. Or maybe it’s just that the people who can afford to aren’t the ones who want to live like hippies, if you get what I mean. The people with hedge-fund money want to live like hedge-funders!”

It’s not clear what the people think of this, or if they are even listening. The man knocks on the load-bearing wall again and says something about maybe knocking it down after doing some reinforcements. Amanda says that’s surely doable and a great idea. Then they turn around and walk back into the hallway. Amanda follows, and I hear them talking about replacing the carpet as they head up the next flight of stairs and into my parents’ room.

They don’t even say goodbye.

The Stager picks up the spoon again and blows on it before putting it to Molly’s mouth. “Have some yummy, yummy soup,” she says.

“They’re going to knock my wall down? And I didn’t know you were going to paint my room. I thought you said it was perfect!”

“It is perfect,” she says. “Amanda is crazy.”

“Well, then, what are you going to do? What are some of the tricks you were talking about?”

“Well, ‘tricks’ might not have been the best word, but you can do little things; like, once, I staged a house where there were a lot of holes in the wall, and I patched them up with toothpaste, then slapped on a coat of paint, and it was as good as new.”

“With toothpaste! That’s so funny! I hope not the kind with blue or red stripes in it! Why were there holes in the wall?”

“Lord knows. The woman was a little crazy. It almost looked like she’d been playing with a nail gun.”

“Really? My God! She might have hurt someone!”

“Well, no, I mean, I don’t think she was actually playing with a nail gun—that’s just what the wall looked like.”

“Oh, I see,” I say, although I’m not sure that I do. Now I am confused about the nail gun and whether the owner is crazy, or the Stager is crazy for saying that woman is crazy when she isn’t, and also if Amanda is crazy for saying that my room needs to be painted, or if the Stager is crazy for saying that it does not.

“Also, there are a couple of things that are sort of like tricks, like the Rule of Three.”

“What’s that?”

“Well, you know how things come in threes?”

“No.”

“Like the Three Little Pigs.”

“Oh! Or the Three Blind Mice?”

“Exactly. And there’s this stager trick that says you should always cluster things in groups of three. Like, on the counter, you should have three asymmetrical objects.”

I know the word “asymmetrical.” It means “uneven.” I’m in the advanced honors reading group. I’m the only one from fifth grade in with the sixth-graders. I get to walk across the tennis courts every day and go to the middle-school building for reading. “What kind of asymmetrical objects?”

“It depends on what room you’re staging. Say, in your front entranceway, you’ve got that pig, and that bowl of tulips, and that African statue. That’s a good cluster. The pig is very small, the tulips are medium height, plus the flowers splay out nicely, and then the statue offsets both of them, tall and thin.”

“The African statue?”

“You know, that tall wooden figure?”

“Oh, the naked starving person?”

“I guess.”

“I don’t know if she’s starving, actually. She might be pregnant.”

“I hadn’t really focused on that possibility,” the Stager says.

“But that’s already a cluster of three objects, so maybe we don’t need you to be the Stager.”

“True. But there are other rooms, and anyway, even though that’s a good c

luster, it’s probably a little too specific to your family’s tastes. A little too … ethnic. Not everyone likes that.”

“But I love that pig.”

“I love that pig, too,” she says.

“If you shake it, it sounds like there’s sand inside.”

“I know. But the rule isn’t just about objects. It’s about things like color. You want to have three different things going on—say, one shade on the wall, another on furniture, and a third for accents, like throw pillows.”

“There were also Three Bears and Three Billy Goats Gruff.”

“Very good. Listen, sweetheart, I really need to go now. Let’s just put the dolls away and clean up all this food.”

“No! We can’t put the dolls away!” I say. “Let’s just feed them some dessert before you go.” I dig around and find a Key lime pie. It’s chewed up pretty badly, too. We both stare at it for a moment.

“He’ll come back. I know he will,” she says. “Rabbits have an amazing sense of smell. They can find their way home from hundreds of miles away.”

I’m pretty sure she’s making this up. “I think dogs are the ones with the good sense of smell, not rabbits.”

“Oh, I don’t know, I wouldn’t be so sure. Rabbits are pretty remarkable creatures. Just think of all the books about rabbits. I wouldn’t be surprised if Dominique shows up at the door any minute.”

I want to believe her. But anyway, if she’s right, Dominique probably ran away on purpose because of the bad smell in our house!

“What rabbit books?” I ask.

“Well … let’s see. There’s a rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, right? And there’s Peter Rabbit, and there’s…”

“Oh! I know, there’s these ones that I love about a rabbit brother and sister named Max and Ruby,” I said.

“I know those books! I love them, too!”

“My favorite is the one about the egg,” I say. “Max’s Breakfast.” I stand up and walk over to my bookshelf to find it.

“I remember that one,” the lady says. “‘Eat your egg, Max,’ said Max’s sister Ruby. ‘BAD EGG,’ said Max.”

“I can’t believe you remember that!”

“My nephew was obsessed with those books. I used to babysit him a lot when he was little.”

I flip the book to the page where Ruby is standing on a chair. She’s wearing a pink dress and tasting the egg. “Here’s my favorite part: ‘See, Max?’ said Ruby. ‘It’s a YUMMY YUMMY EGG.’”

The lady starts laughing, and I do, too. Soon I am laughing so hard I’m having trouble breathing, so I stand up and go over to my nightstand to get my inhaler.

“Are you okay?” the lady asks. “Should I get your nanny? I mean, Nabila?”

“No. I’m fine.”

“Okay. Well, tell me if you’re having any trouble breathing, okay?” She looks at her watch again. “I hate to leave, but my dog…”

“What’s his name?”

“Moses. She’s a girl.”

“A girl dog named Moses?”

“Yeah, it’s actually kind of a funny story,” she says. She unloosens Molly’s braids, finds a brush, and starts to run it through her hair. “The dog was supposed to be named Moose. That’s the name I decided on when I brought her home from the pound. I don’t know what kind of dog she is exactly, but she’s big and a couple of different colors, mostly brown, probably part Lab and part some sort of terrier, and, well, she actually looks a little like a moose—her ears are so big they reminded me of antlers. So, anyway,” she says, “I sent my husband an e-mail at work and told him I thought ‘Moose’ was a good name … But when he got home that night, he said, ‘Hi there, Moses,’ to the dog, and I said, ‘No, it’s Moose.’ And he said, ‘No, you told me it was Moses,’ and we had this fight. Well, ‘fight’s the wrong word…”

“Was there shouting? Or crying? Did your husband lock himself in his room?”

“No, no. I guess I didn’t mean to use the word ‘fight.’ Anyway, we just went back and forth about this for a while, and he was really insistent. It started to become kind of absurd, so we went into the office to pull up the e-mail on the computer.”

“Don’t you have an iPhone?”

“Well, yes, I do now, but this was a long time ago. So I found the sent e-mail and he was right, it actually said ‘Moses.’ And then I realized that my spell check must have changed ‘Moose’ to ‘Moses.’”

“I don’t think it would do that. Maybe you just made a mistake typing.”

“I don’t think so,” she says. “Well, maybe. But anyway, then he…”

“He? You mean your husband?”

“He’s my ex-husband now, although we never bothered to actually get divorced, and believe it or not he’s very expensively on my COBRA right now … Go figure! Sorry, that was sort of inappropriate of me.”

“You have a cobra?”

“No, no, COBRA’s what you call it when you lose your job and need to extend your health insurance for a while.”

“But I thought you had a job. I thought you were working with the Realtor.”

“I am now. But this is a new job. It’s not really a real job. Well, it’s a real job, but…”

“My mom’s phone did that once.”

“What?”

“Her phone changed a bunch of ‘xoxoxo’s to ‘socks.’ I didn’t know why she said ‘socks’ at the end of her message. So I asked her, and she said she didn’t say ‘socks.’ And then it happened again! Do you and your mom text?” I ask.

“No. My mom’s been gone for a long time. Before there were cell phones, even.”

“My God! That’s so sad! My grandma died last year—my mom’s mom, not my dad’s mom. My dad’s mom lives in Sweden. But my mom’s mom didn’t have a cell phone, either,” I say, hoping this might make her feel better, although my mom says two wrongs don’t make a right, so I suppose a second person being dead and not having a cell phone doesn’t make it less bad about the first person.

“She died? I’m so sorry to hear that. Had she been ill?”

“She had Alzheimer’s. She was sick for a long time.”

“Oh my. How rough! It must have been especially hard for your mom, having her in California.”

“We brought her here and had a nurse stay in the house. Her name was Lucy. The nurse, I mean. Not my grandma.” I’m surprised that she knows my grandma had lived in California, but I’m surprised by everything lately, because no one tells me what’s going on. They don’t want to bring up the subject of moving, because they think I’ll get upset, so instead weird stuff like this kept happening—strangers coming into my house, bad smells, and now my rabbit runs away.

“Anyway, it’s become a joke with me and my mom. Instead of saying ‘I love you,’ we just say ‘Socks!’”

“That’s sweet,” she says, but I’m not sure she really thinks so.

“Do you think the girls might want to change into their pajamas after they finish dessert?” I ask.

Before she can answer, Nabila appears at the door. “Elsa,” she says, “it’s time for dinner. Plus, don’t you think you should begin your homework?”

“I don’t have homework today.”

“Elsa, sweetie, I don’t think that’s true.”

Of course it’s not true. I always have so much homework that I can spend my entire life doing nothing but homework. But I don’t want the Stager to leave. I have more questions about her dog; also, the thing about the American Girl dolls is that you can let them sit there like this and not play with them for a really long time, but then, once you get started again, you remember how much fun they are. For a while I was so into them that for every birthday all I wanted were things from the catalogue, and then I ended up with so much stuff! This is a little embarrassing to admit, but at one point I think it might have been true that I had everything there is to buy in the catalogue. I think my mom bought me everything she could, just to make up for the fact that she wouldn’t let me have a dog.

The

lady stands up and adjusts her skirt, which has crept up and is wrinkled. Also, her shirt has come untucked.

“Listen to Nabila,” she says, stuffing her shirt back inside the skirt and yanking the skirt around so the zipper is back on the side, where it belongs. “You should do your homework. I’ll be back tomorrow. If we have time at the end of the day, we can play a little bit more.”

“Do you promise?”

“Absolutely.”

“What about if we bake? Or paint? I have an easel and I have a really nice box of art supplies that I’ve never even opened. Can you paint?”

“Absolutely. Yes. I used to paint chairs.”

“Chairs? Like, you painted the actual chairs, or you painted pictures of chairs?”

“Pictures of chairs. I illustrated furniture.”

“Was it in museums? My dad likes art a lot. We bought a really famous yellow painting in Spain last year, for his birthday. He says it’s his favorite painting in the world and it makes him happy every time he walks in the door because it has such nice bits of light.”

“The one downstairs in the foyer?”

“Yes. Did you paint like that?”

She laughs. “No. I mean, I did just for fun, but for work it was more straightforward illustration.”

“Let’s paint some chairs!”

“Okay, come on, Elsa. Stop being such a chatterbox and let the lady go home.” Nabila has her hands on her hips. “Who did you say you were again?”

“I’m the Stager.”

“I know you are ‘the Stager,’ but do you have a name? What are you doing in here, playing with Elsa? She’s supposed to be doing her homework, and you are supposed to be … Well, I don’t know what you’re supposed to be doing exactly.”

“Nabila, don’t be mean. She’s really nice and she has a dog named Moses and we were just feeding Molly and Kaya some pie.”

“Nabila is right. You should listen to her and do your homework. I’ll be on my way.”

The Stager runs down the stairs quickly, like she’s frightened, and I hope I haven’t said anything wrong. I hear the door slam and I go to the window and see her pull her keys from her pocket and get in her car and drive away.

The Stager: A Novel

The Stager: A Novel