- Home

- Susan Coll

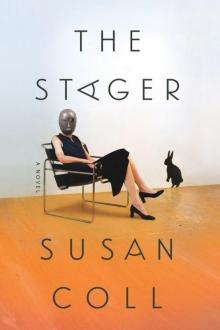

The Stager: A Novel

The Stager: A Novel Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Sophia Musleh, eternal childhood

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Epigraph

Part I: Things from Your Life

Elsa

Lars

Elsa

Lars

Elsa

Lars

Elsa

Lars

Elsa

Lars

Elsa

Part II: Different Chairs

Eve

Part III: Pools of Light

Lars

Elsa

Lars

Elsa

The Stager

Dominique

Acknowledgments

Also by Susan Coll

A Note About the Author

Copyright

4.5BR SINGLE FAMILY HOUSE—BETHESDA

This elegant 4.5 bedroom, 4 full and 2 half bath Flemish Villa sits on 1.5 meticulously landscaped acres in the private, gated enclave known as The Flanders! Overlooking the 8th fairway of a premier golf course, Kew Gardens Country Club, this home provides gracious entertainment spaces as well as comfortable rooms for everyday living! You will have sweet dreams in the 1000–sq. ft. master bedroom suite with ensuite bathroom featuring imported Italian marble, his and her sinks, designer toilets, sunken tub with Jacuzzi! Unwind in the gymnasium or cozy up to the magnificent stone fireplace in the living room or enjoy a gourmet meal in the expansive cook’s kitchen with all new stainless steel appliances! With 6,200 sq. ft., there is no lack of space to enjoy in this home! Only minutes from the area’s finest restaurants in close by Potomac Village or Bethesda! Feast your eyes on the gorgeous grounds featuring a swimming pool, beautifully landscaped stone terraces, private putting green, 3-car garage, and spectacular views of the golf course!

OPEN HOUSE SUNDAY: NOON TO 4 P.M.

PART I

THINGS FROM YOUR LIFE

ELSA

There is a skinny lady with bright red lipstick and purple nail polish standing in front of my refrigerator when I get home after field-hockey practice. Dominique is cradled in her arms, and in her hand is a crooked nubby carrot with the bushy leaf still attached. She is trying to get Dominique to eat the carrot, but he won’t open his mouth.

I don’t know who this lady is or why she is standing in my kitchen holding my rabbit, but since the first FOR SALE sign went up in front of our house three months ago, I’ve gotten used to finding strangers in random places, doing random things: Once, I found a lady sitting on my bed with her shirt unbuttoned, nursing her baby; another time, I saw a man going through my mom’s dresser drawers. One lady even went around the house flushing all the toilets while her husband sat in my dad’s favorite chair in the living room, reading a book.

But no one has ever tried to feed my rabbit before. Dominique doesn’t even like carrots. Also, he looks kind of sick. I’m surprised to see him, since he’s been missing for a couple of days, so I reach for him. At the same time, Nabila walks into the kitchen, sees the lady, and screams. In the chaos, Dominique winds up getting dropped. He hits the ground headfirst, and for almost an entire minute he doesn’t move. I worry that he’s dead, but then, just when I’m about to tell someone to call the police, or the fire department, or my mom, he lifts his head, pricks his ears up straight, looks around the room, and hops out the back door, which is propped wide open—I’m guessing because of the bad smell in our house.

We spend an hour walking around the neighborhood, calling Dominique’s name. We see about ten different rabbits, and even though they all look sort of like Dominique, none of them is him.

LARS

Were Bella narrating this story, she’d lean in confidentially, in a manner that would make you feel that you alone are privy to the secret of my unraveling.

“Lars has been sweating and tossing and pounding his pillows for seven nights straight,” she’d say, “and the dreams he recounts, sometimes shaking me awake at three a.m., verge on harrowing noir.”

Bella actually speaks like this, tossing out phrases like “harrowing noir” with the casual ease of a crack dealer counting hundred-dollar bills. Her thoughts line up in smooth, neat sentences replete with proper punctuation, with just enough emotion to be suggestive of fonts. Without your even noticing, a mini-thesis takes shape, with topic sentences and closing arguments that loop back nicely to echo her chief points. No “um”s or “like”s spill from her lips; her speech is the grammatical equivalent of a military cot.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting my wife is robotic: even in her sleep-deprived fugue, she shows interest in my dreams, asking questions that go right to the heart of complicated narratives that have mostly to do with animals: beaches full of toxic fish, weaponized penguins, a plague of crustacean-like parasites that have invaded our house and cannot be eradicated.

On the fourth day of our trip to London, I awake with a nightmare about a rabbit whose cigar ash has set our house on fire. Later that same afternoon, when we’re doubled down, dealing long-distance with the Dominique debacle, I am troubled by the coincidence; concerned there might be some weird rabbit mojo amok in the atmosphere. Bella explains patiently, as if I am a child, that rabbits are prevalent figures in popular culture, appearing in books and advertisements more frequently than most people realize, and that my dream was likely inspired by Dominique’s destructive habits. He has been quietly ruining our house for years, she reminds me, and this coincidence is surely meaningless.

It can be exhausting to live with someone who always has the answer. I shoot her a withering look. Or at least I mean to; I am no longer sure if my facial expressions convey what I intend.

* * *

BELLA HAS HER own theory about what is going on with me: Buried in the fine print of the three pages of disclaimers that accompany the latest addition to the cocktail of medications she insists I take is the possibility of disturbing thoughts, hallucinations, vivid and unusual dreams, and episodes of psychosis. I’ve always been plugged into the flotsam and jetsam of the universe, and, spouselike (Bella might say witchlike), into my wife’s brain. Some of this manifests as normal, déjà-vu-y stuff, like dreaming about rabbits just before our own disappears, but sometimes I simply know things. And lately I know even more, because things are crystallizing. My eye has become such a finely tuned instrument that I can actually see a ray bounce off the surface material and calculate the degrees of the arc at which it is about to bend back to me. Light carries energy in discrete quantities, and now that I have learned to harness this, it gives me strength.

We argue about this frequently. Bella is a pragmatist. She insists these nocturnal animal visitations, as well as my ability to see, and channel, the light, are merely chemically induced side effects. But she’s wrong: I’ve never felt clearer, and I am finally beginning to understand. I am not as articulate as my wife, and although I am completely fluent and from a highly literate family (my late father was a well-known Swedish mystery writer; you are probably familiar with the whitewashed landscapes and his rugged, brooding, chain-smoking detective, Jesper Johanson), English is not my first language; so when she asks me what it is, exactly, that I am beginning to understand, I cannot explain it to her satisfaction. Only that it has to do with the light. Seeing the light, grasping the importance of diffraction and absorption, embracing the beauty of transparency.

This is something Bella o

ught to understand better than she does, transparency being the centerpiece of her new professional life. You might think I am just casually tossing about metaphors, but four months ago she was actually named the Vice-President for Transparency for Luxum International, the world’s second-largest investment bank. Their new television commercials run in a seemingly endless loop on the cable news networks: “Luxum International = Transparency + Efficiency + Accountability.” Bella had been Luxum’s Vice-President for North American Equity Derivatives for the previous five years, commuting from our home outside Washington, D.C., to New York most weeks, until the company became the subject of a long cycle of unflattering headlines touched off by losing a class-action lawsuit for defrauding investors in risky mortgage loans. This they might have overcome—everyone was defrauding investors, so that was no big deal—but then, that same week, a trader went public with the fact that his team had been siphoning funds to build an underground pleasure palace in Dubai, the sordid details of which were tabloid fodder for weeks and involved underage girls without visas and a room full of goats. Yes, it sounds over-the-top, but I’m telling you, I don’t know what kind of mind could make this stuff up. Part of the recovery involves a massive rebranding effort, and Bella—my personable, articulate, beautiful, brilliant wife, my Bella, who inspires trust among her colleagues—is going to be Luxum’s salvation. The job comes with a mid-six-figure salary, stock options, and the potential for (but not the promise of) astronomical bonuses. The only downside of being Luxum’s VP for Transparency is that we need to relocate to their London headquarters.

Personally, I find this rebranding campaign a bit elliptical. If you aren’t already doing business with Luxum International, you will likely view these commercials with great puzzlement. You might guess that Luxum is in the business of tailoring the sharp Italian suits the actors wear on the commercials, or that they manufacture those slim computers, illuminated with the Luxum logo, that appear on the background desks. Whatever it is that actually occurs beneath the veneer of transparency + efficiency + accountability (and, to be honest, I’m not entirely certain myself), they want Bella badly. They upped the initial offer after she said no on the grounds of not wanting to disrupt Elsa, although I suspect she is really more concerned about disrupting me.

You are only as sick as your secrets. This phrase has lodged in my brain like a splinter, even though I can’t remember where I picked it up. Twelve years into our marriage, four days into our trip to London, to borrow from the lingo of my wife’s former profession, we are so far removed from the lede that we are buried in the jump. We pretend the secret away; we placate it, medicate it, tiptoe around it, construct overpasses and back-road arteries, and we are now in the part of the story that lands in newspapers beside advertisements for convertible sofas and wooden fences and is used to line birdcages or start fires or wrap fish at the dock.

I shake Bella awake and narrate the arc of another hideous dream. I am trembling so badly I may be convulsing. My wife urges me to take another pill. The management of symptoms further erodes the memory, which may in fact be the point. While the sumptuous blue molecules dissolve in my bloodstream, she calls my doctor back in Washington and leaves another voice mail.

ELSA

The lady with the purple nail polish suggests we go to my room to play with the dolls. Maybe she thinks this will make me feel better about Dominique disappearing.

“Molly and Kaya look kind of bored and lonely,” she says, which is of course ridiculous, since they are inanimate objects. But it’s true that they’ve been sitting at their little dining table for more than a year, staring at their kebobs, wearing bathing suits. They are having a luau. The same luau for a year. They are covered in dust, and Molly has slumped into her dinner plate.

The lady picks up a skewer of pineapple. One of the yellow plastic chunks is dented at the center; if you look closely, you can see teeth marks.

“It looks like you have some hungry mice!” she says.

“No, that was probably Dominique. He likes to chew on things. I mean he liked to chew on things.”

Now she looks worried, like she’s waiting for me to cry.

Poor Dominique. I hope he’s found someplace warm to stay. It’s starting to get dark outside, plus it’s colder than it’s supposed to be in April, and I think about crying, but I don’t. Maybe I’m less upset than I should be about him being gone. Dominique was an unhappy rabbit who never seemed to like me very much. He bit whenever I tried to pet him. He didn’t seem to like our house. He gnawed on the legs and gashed the fabric of an antique velvet chair that was some sort of family heirloom. We found him hanging from the living-room curtains like a monkey—he must have leaped up and gotten his claw stuck in the lace, which he shredded in the process. He bit my parents and they took him to a doctor, who said he didn’t like being cooped up in our house. Then my mom bought a cage, but I let him out whenever they weren’t home. Instead of being grateful, though, he just destroyed more things—like, last week, he’d eaten a hole in the living-room carpet and thrown up bits of white wool, which was weird, because rabbits aren’t supposed to be able to vomit. Before my mom left for London, she’d asked me if I was trying to make it so that no one would want to buy our house, which hadn’t occurred to me at the time, but was not a bad idea.

The lady finds the box with all the toy food in it and dumps it on the floor. She then sifts through the enormous heap of stuff, stopping to study the sushi platter and the hamburger buns and each little cereal box like these are the most amazing things she’s ever seen. She gets all excited about the chicken-noodle soup, for some reason, and then she digs around until she finds the tiny can opener. She’s really into this, the way she clamps the blade onto the side of the can and turns the handle and pretend-pours it into a small plastic bowl. Then she takes a spoon and blows on the invisible soup and feeds it to Kaya, who is wearing the same blue-and-white polka-dot bikini I’d changed her into a year ago. I prop Molly back up in her chair so she can eat some soup, too. She’s wearing a tie-dye one-piece under a sarong. Her hair is in two braids, one of which is caught in the strap of her bathing suit. As I fuss with her, I stir up so much dust I’m embarrassed. People clean my room once a week, but my mom told them never to touch the dolls. That’s because the cleaning lady who used to work here before we got a new cleaning lady once dusted Molly’s horse and his saddle fell off. When she tried to fix it, a stirrup broke, and then the cleaning lady had to leave the country. I’d asked my mom if she had to leave because of the broken stirrup, but all she said was “Don’t be silly, Elsa!”

* * *

WE’VE ONLY BEEN playing for about ten minutes when the lady looks at her watch and says, “Oh my! It’s later than I realized, and your nanny said you had homework to do. Plus I need to get home to walk my dog.”

I don’t understand who this lady is or why she’s here, playing with me. I’m not even sure if I like her, but I don’t want her to leave. “I don’t have that much homework,” I lie, “and anyway Nabila is not my nanny. She’s my friend, plus she does my laundry and drives me to school and stuff. But … wait, who are you?”

“I told you when we were downstairs, remember? I’m the Stager. I work for Amanda.”

Amanda is the Realtor. She is helping us sell our house so we can move to London. She always dresses perfectly. Her business card says Amanda Hoffstead Always Cinches the Deal! We are all afraid of Amanda, but my mother says that her being intimidating is possibly a good thing: maybe people will be frightened into buying our house this time around. A different lady already tried to sell our house, but no one wanted to buy it, so after three months, when her exclusive was up, we had to relist.

“I know you are the Stager, but what are you actually doing?”

“I’m just fixing up your house to get it ready to go on sale, to make it so other people can imagine themselves living here. Nothing too major. Your room is fine, really—it’s actually perfect, the best room in the house—so all

we need to do is tidy it up a bit, put the dolls away for starters.”

“Well, if that’s all you’re going to do, then it sounds like you’re just a cleaning lady.”

“Touché.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means you have a good point. But I’m meant to do a little more than put things away. It’s actually a creative job.”

“It is?”

“Well, it’s more creative than you might think. I’m kind of new at this; I’m just doing it on the side. I’m really an artist. Well, I was an artist, before I became a journalist. Now I’m … Well, I don’t even know what I am anymore. An unemployed journalist, I suppose.”

“No way! My mom used to be a journalist! She wrote about money. But now she makes money. Or helps other people make money. Or helps people behave when they make money. That’s why we have to move to London.”

I don’t want to move to London, but no one seems to care. Everyone keeps saying how exciting it is, and that soon I’ll be speaking with a British accent. And drinking tea and eating scones. I’m really tired of the whole London thing and we haven’t even moved yet.

“Well, I’m not exactly a journalist anymore, either. I was running a magazine until a few months ago.”

“Oh. Like People?”

“No. It was a shelter magazine.”

“A what?”

“A magazine about homes.”

“I didn’t know there were magazines about homes.”

“Not so many anymore, which is why I’m sitting on the floor playing with dolls!”

“So what else are you going to do with my house?”

“There are lots of little things I need to do. And I have to work very quickly, since your open house is on Sunday.”

“But it’s only Tuesday.”

“Yes, but there’s a lot to do.”

“Like what?”

The Stager: A Novel

The Stager: A Novel