- Home

- Susan Coll

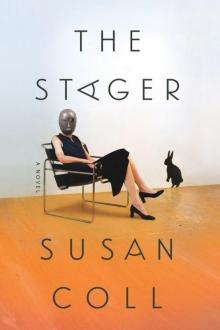

The Stager: A Novel Page 6

The Stager: A Novel Read online

Page 6

“To each his own,” Diana says. Then she picks up her tray and goes to sit with Zahara and leaves me alone with an entire sausage pizza, which at first seems like a good thing, but after I take a bite I feel the grease ooze down my throat and realize that Diana has ruined it for me. Then, even worse, after school, Diana acts like she actually enjoys running laps at field-hockey practice. Usually we run together, although we don’t really run, we walk until the coach notices we aren’t running and he yells at us. Then we run a little bit until he looks away again. But there she goes, up ahead with Zahara, who is the fastest runner in our class, and that makes me move even more slowly. After a while, I just stop. The coach yells at me and says if I don’t try harder I won’t be eligible for the team when we get to middle school next year, and I say big deal, I’m moving to London anyway.

I sit down in the middle of the track.

The coach comes over and asks if I’m okay, and even though I am, I know I’m about to get in trouble, so I say I’m having difficulty breathing and that I need to go back to the main school building to get my inhaler. When I get there, I open my locker, find my inhaler, and take a fake puff. By then it’s almost time for Nabila to pick me up, so, rather than go back to the field, I stand in front of the school to wait.

* * *

NABILA THINKS IT’S important that we talk each day. On the way home she asks me the usual annoying questions about school: what did I learn, what did I have for lunch, did I have a lot of homework. Fortunately, she doesn’t ask me about field-hockey practice, because I know she won’t be sympathetic. She always talks about how exercise is good, and sometimes after school she even proposes we go for a bicycle ride or a walk. I don’t want to have that conversation.

When we arrive at the driveway, I see the Stager painting the front door. I roll down the window and shout to her: “Hey, what are you doing?”

“She’s painting the door,” Nabila says, as we pull into the garage.

“Yes, I know that, but why is she painting it white? It looked good black.”

Nabila shuts the garage door behind us, using the automatic opener. “You need to let the lady do her job,” she says. “The lady has a lot of work to do to get the house ready to sell.”

“I know that, but…”

“I spoke to your mum again, and then I spoke to the lady, and everyone agrees it’s a good idea for you to just let her do her job.”

“Yes, I get it. But I am letting her do her job! I just want to know why she’s painting the door white!”

“The first open house is in four days. The lady does not have time to be your babysitter.”

“God, Nabila, you are being so mean! The lady has a name. It’s the Stager. Well actually, it’s also Eve Brenner. And I know she isn’t my babysitter. Anyway, she’s the one who wanted to play yesterday, not me.”

“Okay. Let’s change the subject and go have a snack, and you can think about what you’d like for dinner. Oh, also, your mum said to tell you she’s going to be on the television tonight. And she’s wearing your favorite dress. She said she already taped the show and she blew you a secret kiss, so you should watch very closely and you’ll catch it.”

“Big deal. She’s on television all the time, and if she means the green dress with the stripes, it’s not my favorite anymore. I get embarrassed when she leans forward and I can see her bra and so can everyone else who’s watching TV. What about my dad?”

“What about your dad?”

“Did you talk to him?”

“No, sweetie.”

Nabila is digging around in her gigantic bag, trying to find her house key. Her purse is always a mess, like the Stager’s. I once counted and it took her nearly a whole minute to find the key, which is not a good safety practice, especially since the garage light automatically goes off after a minute. I once told Nabila she should wear her key around her neck, so she could find it quickly in case a criminal was hiding in the bushes or, in this case, inside the garage, but she didn’t listen, and now I’m thinking maybe I can do Nabila a favor and organize her purse for her, too. I wonder if the Stager has even noticed what I’ve done for her purse, but she might not have had any reason to look inside or use her wallet if she’s been at the house doing her staging all day.

“I won’t bother her, but I just want to know why she’s painting the door white, and also what rooms she staged today.”

“I’m not sure. Until I left to pick you up, she was mostly in the front hallway and the living room and the kitchen.”

“Is the smell gone yet?”

“Funny you should ask. It was gone. I thought the Stager fixed that horrible garbage smell, but now either it’s back or there’s another smell. I hadn’t noticed it until today.”

“Is it the same smell?”

“It’s the same but different.”

“Better or worse?”

“I don’t know if you can quantify how bad a very bad smell is. Sometimes I smell it and sometimes I don’t, so maybe I’m imagining the smell. Who knows, maybe I’m losing my mind.”

I hope Nabila isn’t going crazy, too.

“Well, maybe it’s good that our house smells bad, because I don’t want anyone to buy it. I don’t want people knocking my wall down and painting my room some other color, and I don’t want to move to London. Will you come to London?”

“We already talked about this, remember? I’m going to university here, so I can’t go with you. But you’ll find a new friend in London. And maybe I can visit you sometime.”

“I want you to come.”

“I know, honey.”

“I don’t want to move.”

“I know. I understand. Moving is very hard, even for grown-ups. I had to leave my country to come here, and I miss my own mum and dad every day. But look, at least you aren’t going to leave your family.”

“Maybe I could just stay here with you and we could keep the house.”

“I like that idea, but unfortunately life doesn’t work like that.”

“I have to leave my room, and my friends, and you, and Dominique is probably dead and I’ll never see him again.”

“Don’t be morose. He’s probably fine. I’m sure he’s found a lot of rabbit friends by now. Maybe he’s hopped back to his own family!”

“No, he came from a farm in Frederick, don’t you remember? Or maybe you weren’t here yet. Maybe that was Adriana. Or Fatima. Or wait, maybe it was before her … the girl from Romania. Anyway, Frederick is, like, an hour away, so I don’t know how he could have gotten that far.”

“You never know. Rabbits are good hoppers.”

“Not Dominique. He’s not that good a hopper, plus I’ll bet he just bites all the other rabbits anyway.”

Nabila laughs, but I’m not trying to be funny.

She finally finds her key and is about to stick it in the door when the light switches off, and we just stand there for a moment in the dark.

* * *

ALREADY THE HOUSE looks different. The painting that we bought in Barcelona, the one that hangs above the table where my parents always put their keys when they walk in the door, is gone. My dad is going to have a meltdown. Not only does he love that painting, but it cost a lot of money.

I keep staring at the space, trying to figure out what else is wrong, and then I see the green table is gone, too. There’s a different table there that looks familiar, but I can’t say why. Then I realize it’s the table from the living room. Now there’s a mirror over the table instead of the painting. And the mirror is from … I don’t know. I’ve seen that mirror before, though. Maybe it was in my parents’ room once, and then it got put in the attic?

And the pig that I love is gone! The naked starving person/pregnant lady/African statue, too! The bowl of tulips is still there, but it’s alone, so now there is no cluster of three. For almost my entire life, there has been the green table and the pig and a vase of flowers (but not always tulips), the naked starving person, and then, since last

year, the famous yellow painting, and now it’s all gone.

Also, the kitchen is all wrong. Everything has disappeared. All of the pictures on the refrigerator—me at the beach with my cousins from Sweden, and the schedule that tells me when I have field-hockey practice, and my last report card. I look at the counter and can see that my dad’s coffeemakers are all gone, too. Even the toaster has disappeared. Suddenly I love and miss my toaster and I want to have a Pop-Tart for my after-school snack, but how can I do that without a toaster? I think I’m going to cry again, which is really ridiculous, so I decide that instead of crying I will just fix this situation. I open the cabinet and find the toaster, which has the cord wrapped around it neatly. I put it back on the counter, unwind the cord, and plug it in. Then I open all of the cabinets until I find the coffeemakers, and I put those back out, too. Once everything is where it belongs, I climb onto the counter and stand up so I can reach the higher shelves. I begin to look for Pop-Tarts, but everything is in the wrong place now—all the cereal boxes are on their sides instead of standing straight up, and the cans of tuna are stacked one on top of another—and I can’t find anything.

I hear someone enter the kitchen and turn to see the Stager passing through on her way to the basement. She has the can of paint in one hand, and holds the brush over it, to catch the drips.

“Hi, Elsa,” she says, but she doesn’t stop to talk to me, or ask how my day’s been. She doesn’t even comment about me standing on the counter with my muddy field-hockey cleats on, or about the coffeemakers and the toaster being back out again.

“Hey, why are you painting the door white?” I yell to her as she walks down the stairs. “And why are you going downstairs?”

“I’m painting the door red,” she says.

“But it’s white!”

“That’s the primer. You have to put a coat of primer on to get it ready for the new paint. Also, it will help cover up the black.”

“Oh.” I don’t really understand why you’d put white on black before putting on red, or why you’d even put red on in the first place when the black looked perfectly good.

“After it dries, I’ll start layering on the red. I’m just going downstairs to wash the brush in the laundry-room sink.”

“But why?”

“Because it’s full of paint.”

“No, I mean why red?”

“Oh, it’s just another staging thing. Mostly because it’s a cheerful color. It’s eye-catching, it has curb appeal. But there’s some symbolism, from what I’ve read. In some cultures—maybe Ireland?—it actually means the mortgage has been paid and the house is owned free and clear. And in feng shui it means stability and fortunate rest inside.”

She’s halfway down the stairs now, and I want to keep her from disappearing into the basement.

“What’s feng shui?”

“Oh, just some Eastern-religion design thing.”

“Do you know if we have any Pop-Tarts?”

“I don’t know, darling. Ask Nabila. I’m sorry, but I really need to get back to work. There’s a lot left to do, plus I have another appointment later today, so I’m in a bit of a rush.”

I wonder if her other appointment has to do with Vince and the loft. I wonder, too, if it involves another girl, maybe one who likes to run laps at field-hockey practice or who has a better collection of American Girl dolls. I ask her who Vince is, but she doesn’t answer, so I shout another question. “Hey, what did you do with the pig and the naked starving person?” But she’s already all the way downstairs, and I can hear the water running in the sink in the utility room.

* * *

I KNOW WE have Pop-Tarts, somewhere, so I take everything out of the cabinet to see if they’re way in the back. The counter is getting crowded with food, and a box of crackers falls to the floor. Looking at all this food is making me hungry. I think maybe I should stop trying to find the Pop-Tarts and just eat the crackers, or maybe have a bowl of Froot Loops, but I’ve already taken the toaster out and feel weirdly like I need to use it, so I keep looking. There’s a lot of ramen soup, like almost a hundred packages, but I don’t particularly like ramen soup. None of us really do, but my mom says she keeps it for emergencies.

Maybe the Pop-Tarts are on the very top shelf? Even standing on my tiptoes on the kitchen counter, I can’t see what’s all the way up there, but I can reach it with my hand, so I just start pulling stuff down, and some of it’s heavy, like the bag of flour that falls, almost knocking me down. It splits open, and there’s flour everywhere. Still no Pop-Tarts.

Nabila comes into the room and stares at me.

“What in the world are you doing?” she asks.

“I’m looking for a Pop-Tart.”

“A what?”

“You know, a thing you put in the toaster and eat for a snack. Or for breakfast, maybe. They have different kinds, like chocolate, or strawberry, or ones with sprinkles … I know we have some. I know we used to…”

“My God, Elsa. What are we going to do with you?” She opens the freezer door and pulls out a box of Hot Pockets.

“No, silly!” I find this hilarious, confusing Pop-Tarts and Hot Pockets, and I start to laugh, but now Nabila is clearly furious, and I feel bad, since where she comes from not only do they have scrawny rabbits, but they apparently don’t have Pop-Tarts, either. I realize that I don’t even know what country she’s from, but this doesn’t seem like the best time to ask.

“Look at this mess you’ve made!”

“It’s not my fault,” I say, even though it is, sort of, although if someone had put the Pop-Tarts where they belonged and closed the bag of flour properly this wouldn’t have happened. There’s white powder pretty much everywhere.

“What’s gotten into you, girl?” Nabila asks. “I’ve been with you for almost a year now and I’ve never seen you behave like this.”

“I’m not behaving like anything. I just want a Pop-Tart. Why is everyone being so mean to me?”

“Okay, I get it. Your mum and dad are away, and that’s tough. I understand that myself. I haven’t seen my own mum in two years. Also, this moving stuff is very hard. Maybe you’re upset because the lady is changing everything around here. Your mum explained this to me.”

“What about your dad?”

“What about my dad?”

“Why don’t you miss your dad?”

“Well, I do, darling, but he’s been gone six years.”

“Gone where?”

“Gone. Gone.”

“Did he have cancer?”

“No. The warlord came to our village and…”

Now I burst into tears.

“Oh no, darling. I understand, I really do. On top of everything going on, your mom said you might be getting a little moody, between the move and your body growing so fast.”

“I am not moody!” But maybe I’m a little moody. And it makes me even moodier to think of my mother and Nabila talking about my body. But really what makes me cry is the word “warlord.”

“Oh no, Elsa, please don’t cry. You’re such a big girl. Your mum will be home at the end of the week, and probably she’ll bring you a present. And she said the new house is so nice, you’ll have a lovely big room all to yourself, and a pretty garden…”

“I already saw a picture of my new room and I don’t like it. And I already have a lovely big room all to myself, here. And we won’t have a pool. And there’s a stupid stone rabbit in front of the house that’s going to make me think of Dominique every time I see it. And I don’t miss my mom, so I don’t know why you’re talking about her. I’m crying because…”

“Elsa.” She comes over and puts her arms around me, but I push her away. She looks startled, like she might cry herself. “I don’t even know what to say to you anymore, Elsa.”

“Don’t worry, Nabila, it’s not your problem. I’m going to clean this up and do my homework. I’m just going to go downstairs to get the vacuum.” But I’m not really going downstairs to get the vacuum.

I’m going downstairs to find the Stager, even though it occurs to me that it wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world to try to make Nabila happy, to just go get the vacuum and clean up the mess.

On my way to the utility room, I pass by Nabila’s room. She’s left the light on, and when I look inside I remember how small and dark it is in here. She doesn’t even have a closet, so her clothes are either piled neatly in stacks on the floor, or hanging from a rack. We have two empty bedrooms upstairs, and I wonder why she doesn’t just move into one of those.

Her bed is unmade, a wet towel is lying on the floor, and her jeans are crumpled on the chair. I decide to do something nice for her to make up for being so mean, so I clean up a bit. First I make her bed, then I pick up the wet towel and put it on the hook behind her door, and then I pick up the jeans, which are perfect; they’re just the right color of faded denim. They’re so long that when I hold them up they’re almost as tall as me. When I begin to fold them, something falls out of the pocket.

It looks like a baggie full of smashed-up leaves, or maybe even tea, which is what I think it is at first, until the word “marijuana” pops into my head from the unit we did at school on “harmful narcotics,” which was right after the unit on “stranger danger.” It seems pretty unlikely to me that Nabila would do any harmful narcotics, since she’s always talking about being healthy and eating fruits and vegetables. She’s become friends with the guy who works across the street, at the farmstand in front of Unfurlings, and she’s even convinced my mom that it’s better to buy the vegetables there than in the grocery store because they don’t use pesticides. I open the baggie and smell the leaves, but I don’t know what marijuana is supposed to smell like, so this doesn’t help.

Someone knocks on the back door. I hear the Stager open it, and she starts talking to a man. Then I hear another voice, and then another, and then Nabila comes downstairs to see what’s going on, and all of a sudden there are three men in the basement, carrying equipment. I don’t know who they are, but one of them has a video camera that says “HGTV” on the side, and he’s standing outside Nabila’s door, talking into a microphone.

The Stager: A Novel

The Stager: A Novel