- Home

- Susan Coll

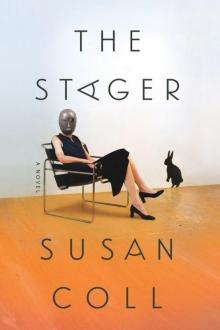

The Stager: A Novel Page 7

The Stager: A Novel Read online

Page 7

“And now we journey to the leafy suburb of Bethesda, Maryland, located just outside Washington, D.C. Forbes magazine has named Bethesda one of the most affluent and highly educated communities in the country. CNNMoney has listed it first on top-earning American towns, and, most intriguingly, Total Beauty has ranked it first—and, yes, I did say first, ladies and gentlemen—on its list of the country’s Top Ten Hottest Guy Cities … This is of course a nice segue into the home of a celebrity couple who wish to remain anonymous, which is why they have chosen to live in relative obscurity in a tony enclave of million-dollar-plus homes known as The Flanders…”

The camera is pointed at me, and I cling to the baggie, terrified that I’ve just been caught on camera snooping and holding drugs.

I stuff the bag of leaves in my pocket and squeeze past the HGTV people into the main part of the basement, where the door leads out to the pool. A blur of white races across the garden and squeezes under the fence. The next thing I know, I’m outside, where it’s raining, with a bag of smashed-up leaves in my pocket, chasing after a rabbit that might or might not be Dominique.

LARS

Bella is in the middle of another important dinner when she learns that Elsa is missing.

We had originally planned to make this our big London date night, to dine at some five-star fusion restaurant in Soho she’d heard about from a colleague, but then she remembered that she had a work-related “thing.” This is not atypical Bella behavior. Sometimes when we have plans, her memory is jogged at the last minute by a chirp of the calendar function on her phone, other times by a flip through her pocket diary. Another method involves smacking herself on the side of the head as she recalls suddenly that she has another obligation. Last night it was dinner with Luxum’s CEO; the night before, drinks with the outside counsel in from Frankfurt. Tonight is the marquee event, an expensively catered welcome-to-London-I’m-the-face-of-Transparency-at-Luxum-International dinner with various dignitaries, celebrities, and big-time investors. How one forgets about this until an hour prior to the event is something that eludes me.

And there she is, seated between the visiting prime minister of Kazakhstan—or maybe Kyrgyzstan (I am reasonably well traveled, but my experience is confined to places where I have either lived, played tennis, or vacationed)—and the boozed-up American ambassador, who seems to be hitting on her.

Bella can see on her phone, which she pulls discreetly from her jacket pocket a couple of times as it vibrates, that she’s missed several calls from home. (This is where I begin to understand what I was beginning to understand back in the hotel room when I could hear her talking on the phone even though maybe I could not. I have a working theory about why this is possible, but I’d like to string it out a few paragraphs longer to be certain it is true.)

Bella is beginning to worry, but not overtly. Right now it’s just a low-grade worry, the equivalent of a dull toothache. She tells herself that it’s probably just Elsa calling with more field-hockey shenanigans; the coach has already e-mailed us to say that we need to meet to discuss the problem of our daughter when we return. Or maybe there’s simply a homework-related question, or the violin teacher needs her check, which Bella now realizes she has forgotten to write, or perhaps there’s some update on the Dominique situation. Then Bella’s assistant comes in, a stunning young woman of South Asian descent. (Might I note, perhaps irrelevantly, that Bella’s assistants are always lovely? If I had to speculate, I’d say this is her way of demonstrating that she is confident enough in her own skin to surround herself with beauty.) She taps my wife on the shoulder to tell her that her estate agent from the States is on the phone, and that, unable to reach Bella by cell, she’s called the office directly to report a real-estate emergency.

Bella’s train of thought goes something like this (and please note, this is not a verbatim transcript, because her thought process is interrupted by the hullaballoo in the background, the ambient sounds of people who want a minute of her time as she struggles toward the exit, of clanking silverware and dishes being collected by waiters, as well as overheard snippets of conversation, which I have edited out for the sake of brevity): A real-estate emergency? This Realtor is one high-maintenance piece of work, what with her constant phone calls and her demand that I fork over thousands of dollars to have the house professionally staged.

Nevertheless, Bella is relieved to have a reason to leave the table, even if it means forfeiting the yellowish puréed vegetable soup that looks, and smells, pretty good.

I’m dozing intermittently, while watching some silly British sitcom, when I realize with alarm that something is wrong with this scene. It was one thing to sort of be inside Bella’s head when she was a few feet away and I could hear snippets of her telephone conversation with the doctor, but now she is all the way across town and I am in bed in our increasingly fetid hotel room, wearing only my boxers.

I bolt upright: this point of view is not meant to be! I wonder if this condition might have something to do with the light. Up on the roof, helping Jorek earlier that day, perhaps I absorbed too much sun.

Praxisis. The answer is always Praxisis, even when it isn’t answer “b.” I conjure an image of the lovely vial, slim and cylindrical, the perfect repository for my treasured pill, and try to remember when I popped the last one—was it this morning, before I’d gone off to meet Jorek, or have I taken one since? Truly, I cannot recall.

I anticipate the bliss, the battle forged as the molecules dissolve in my bloodstream, their tiny swords slaying the enemy. If only, like infatuation, there was a way to make this last forever! I know too well that it does not, that the Catch-22 is the massive anxiety caused by thinking about the ephemeral nature of the bliss. That, plus the fact that I will soon run out, and I am under the impression that Praxisis is not attainable in the U.K. It is counterproductive to overthink this situation, and it’s clearly sometimes best to throw caution to the wind, to travel without a map, to avoid the limitations of too much left-brain planning. Accordingly, I make my way to the bathroom, wrestle with the child-safety lock, triumph after a few false starts, and swallow a handful of pills, mixing in a couple of Zuffixors for good measure. I can no longer remember what they are meant to do. Then I return to bed and wait to be enveloped in Praxisisity.

It is even slower than usual to arrive, however: an emerging problem is that I am building up a tolerance, and the Praxisis, even in higher doses, is taking longer and longer to kick in. Unsurprisingly, this situation is generating its own vicious anxiety cycle. What if it eventually stops working? Is it really too much, God, to ask for a drug that works the way it is supposed to, without endlessly sprouting newfangled complications?

Slowly, slowly, I feel it working, but now with a new Praxisis twist: when I turn my dial back to the dinner party, this time I am not just inside Bella’s head, but I am inside the heads of everyone she can see from her point of view. Interesting, perhaps, yet the cacophony of these disparate, random voices is almost deafening.

A hefty, balding man in a gray suit seated at the left corner of Bella’s table summons the waiter and asks him to refill his glass with wine, even though he knows that he’s already had too much to drink. He’s desperate to sneak out for a smoke, notwithstanding the fact that he’s quit, or sort of quit, or at least promised his wife he’s quit. But he has problems—liquidity, a delinquent kid, an aloof wife—and who can blame him for needing a little nicotine crutch? At the far end of the table, the actor who’s currently performing as Hamlet in a much-acclaimed West End production is worrying about his weight, although he understands, rationally, that this is ridiculous. Still, he shreds the bread on his plate and rolls a small bit between his forefinger and thumb, then drops it in his mouth, takes a sip of water, and feels the yeasty glob inflate. Bread is healthier this way, he tells himself, and more nutritious, because it is both food and beverage at once. Besides, he’s an edgier performer when at his most stick-thin.

I can hear, or feel, or sense, th

e waiter sneer as he clears Hamlet’s untouched soup. He has his own problems, this waiter. Would it be insensitive of me to say the waiter’s problems are of the usual waiter sort? He is, indeed, a frustrated actor himself, and he thinks he’s a better actor than this anorexic Hamlet, whom he considers something of a hack.

Why, for the love of God, am I privy to all of this private chatter? Does such knowledge require me to care? But, more to the point, what am I meant to do with the painful realization that Bella has not invited me to this dinner? Yes, of course, she has dinners most nights, and I rarely attend, and that’s fine by me; these dinners can be dreadful, especially when people ask me what I do. Since I feel obliged to come up with an answer more substantive than that I am lately engaged in ordering high-end gadgetry on line, I tell them I used to be Lars Jorgenson, Wimbledon semifinalist, a whirling dervish in Tretorns, and then they light up, and then they take a good look at me and go dim.

But now that I am inside her head, I can see that this event is not so run-of-the-mill. This is Bella’s official welcome dinner, and though I don’t claim to know the etiquette, it seems to me this ought to have been a spousal affair. The insult sort of fells me; it’s a physical reaction that causes me to draw the curtains again, even though, now that it is nighttime, there is no light.

* * *

IF I AM to attempt to deconstruct the strangeness, I need to back up to a point earlier in the day when I’d been helping Jorek on the roof. I am able to isolate in that scene a moment of pure joy. It had to do with my sense of purpose, I suppose: I loved being useful, helping Jorek with his tasks, hauling his equipment up the ladder, fetching his tools, popping over to the store to get an extension cord, going to the deli to buy us both lunch. I am in awe of Jorek, and strangely attracted to him, although let me again emphasize that this is entirely nonsexual in nature, and even if it was otherwise, skinny old Jorek, with his belt drawn tight to hold up his too-big jeans, and his very crooked teeth, is not someone I would find particularly physically compelling. Maybe it’s simply that he lavishes me with attention, he’s the friend I don’t have. Or maybe it’s more elemental, and simply has to do with an admiration of his prowess with power tools.

Up on the roof, I pleaded with him to let me have a go with the chainsaw, which he finally did. It was harder than it looked, holding steady this heavy, vibrating, thrumming instrument, forcing its blade into the tar of a shingle. The sun was beating down and was far more potent than it looked. Despite my insistence to the contrary about the lack of light, etc., I’ll admit, without prejudice, that I should have worn a hat.

Somehow, and perhaps because of what was beginning to feel like possible sunstroke, I lost my balance and accidentally bore down with the blade in the wrong spot, creating an unfortunate gash just beside the gutter. Don’t laugh! It is harder than it looks; trying to keep the blade steady is, I imagine, not unlike wrestling an alligator or riding a wild bull. I teetered inches from the edge and could see, below, daffodils in blooms, and that stupid stone rabbit, and I imagined myself falling, falling, falling, and I wondered where I’d land and what I’d break and whether anyone would take care of me if I wound up in traction, or would miss me if I died. But just as I was about to plunge, there he was, his surprisingly strong hands around my waist, wrenching me back to the land of the living.

Jorek, my savior.

Later, he told me that I’d fainted, and that he was in the process of calling an ambulance when I’d finally come to, but I think he might have been embellishing this part of the narrative a bit, perhaps to make himself seem more heroic.

We hadn’t entirely finished for the day when Jorek’s wife called and urged him to hurry home. She was roasting a chicken and baking a pie, and some cousins were coming for dinner. I asked a variety of questions about the meal and about his family, pining for an invitation, but none was forthcoming. I wondered if Jorek had even told his wife about me, or if, as for Bella, I was some shameful secret.

And now I wonder if I can conjure Jorek at his dinner. I think hard on Jorek, on his family and the chicken and the pie. I meditate on the smell of a broiling onion and some potatoes basting in the juice of the bird, to no avail. Just the thought of a home-cooked meal, even if I can’t get a whiff, makes me hungry, so I return to Bella’s dinner, hoping that perhaps my new superpowers might enable me to co-digest.

They do not. Instead, I am back in the static of her head. She is engaged in a very boring struggle to remember correctly the name of her own assistant. Is she Priyavishnu, or Vishnupriya? By now she has arrived at her office, one floor below the banquet room full of dinner guests, and she is preparing to take Amanda’s call. She wants to thank her assistant by name, but she hesitates. Names, there are too many names! She’s having trouble keeping in her head the names of several of the men at the dinner as well, and has devised a strategy at least to differentiate them, based on the patterns of their ties. Yale stripes is the visiting CEO of a Korean media company for which Luxum manages funds; leaping fish is an important solicitor at a large London firm; deep blue matches the eyes of Luxum’s head of human resources based in New York, who just happens to be in London on holiday with his family. (Bella entertains the fleeting thought that he’s attractive.) There are other important people in the room she ought to be fêting more aggressively, but they sport mostly a variety of tactful, unremarkable stripes, and hence she can’t remember their names or their roles. To get her attention right now requires something fairly astonishing, as I know from my own experience. Animals with bows and arrows, or disconnected body parts. I try to tell her this, to make a joke, but it seems our mind-meld extends only one way. Bella and everyone around her have become transparent. But transparent only to me.

I am then seized by a sudden, distressing thought. Perhaps Praxisis is not my friend, but my enemy. Not the solution, but the problem itself. Perhaps Bella is actually onto something after all, with her relentless harping on side effects. Making my way to the bathroom, I gather my collection of pills and then dump the lot on the bed. I study the label on each vial and then plug the data into Google, first individually and then in various combinations. Praxisis + Zuffixor + Romulex + Luxemprat = dizziness and nausea, insomnia and diarrhea, and frequent but unsustainable erections. In some cases, where the dosage of Praxisis exceeds five hundred milligrams and is taken in conjunction with Texicor and Ciraxes, strokes may occur. Zuffixor + Volemex = mostly the same as the above, with the addition of migraines and a sense of desolation and despair. Zaxivon + Amulerex = weight gain, strange food yearnings, miscarriages, and a burst of euphoria frequently followed by suicidal thoughts. Nothing unexpected or out of the ordinary there.

I continue to play with the combinations, varying the dosages to see what comes up, and finally I stumble onto the website of The German Journal of Medical Metaphysics, and it speaks to my condition, which is a huge relief, since, for a moment there, I was thinking I am possibly losing my mind.

Apparently, when a certain dosage of Luxemprat + Zumlexitor is followed by a thousand milligrams of Praxisis, “in some rare cases, the combination of these particular serotonins, painkillers, and anti-anxiety medications containing a surplus of the letters z and x have been known to result in the development of a limited but omniscient point of view.”

I’m not entirely sure what this means, but it doesn’t sound good.

I consider calling Bella, since she is one of those people who always rally in a crisis, but she’s already on the phone and I’m already inside her head, where she’s reflecting on something she once overheard on a train, a stray fragment of dialogue that has stuck with her for many years. A man, a dull bureaucrat type, unmemorable but for this interesting snippet, had quipped to his seatmate that he’d never experienced pain, that he’d never had so much as a headache. This seemed to Bella frankly unbelievable, but later, when she reflected on it, her own version of being superhuman was that she’d never, before now, felt real stress. Things arose, problems needed solvi

ng, complications sometimes became extreme. But there was always a solution, and the trick, Bella thought, was to see life as an ocean, to stay atop the waves. There would always be another Davos on our anniversary, another Aspen on Elsa’s birthday. She did the best she could, and avoided getting caught in sentimental traps. She forgave herself her shortcomings and mistakes. Even when the mistakes were not forgivable.

It’s interesting to know this suddenly about my wife, but it also feels mildly invasive. Although not quite as invasive as reading her e-mails, which is something I once did, for a brief interval, and what I learned nearly made me blind. As much as I abhor the darkness, there is definitely such a thing as too much light.

* * *

BELLA PICKS UP the phone. “Amanda, greetings!” she says cheerfully, while at the same time bracing for bad news, like maybe the house has just failed a termite inspection, or crumbling Chinese drywall has been discovered, or a sump pump has stopped working, leading to a flooded basement, which happened a few years ago, destroying three of my exercise bicycles and a new flat-screen television that had just been delivered and was still in the box.

“I’ve been trying to reach you for an hour. I tried calling your hotel, your husband, your nanny, and your cell … I hate to disturb you at work—your assistant said you were in the middle of some important dinner, and I’m so sorry—but I’m a little worried.”

This is what the Realtor says. Or what I think she says. My point of view is omniscient but limited. My knowledge of the conversation is being strained through Bella’s brain, and it’s possible that bits of information, like lemon seeds, are getting stuck in the mesh.

“Worried about what?”

“Both the front door and back door were open when I got here, and there’s no sign of anyone home except for the camera crew.”

“What camera crew?” Bella feels a small jolt of terror. Or I think she does. Maybe I feel a small jolt of terror and am projecting this back onto her. (Now that I am inside her brain, I’m having trouble telling which part is her and which part is me, although, in truth, even before these powers emerged, my inability to separate myself from Bella has always been a problem.)

The Stager: A Novel

The Stager: A Novel